RESEARCH

PublicationsStudy Opportunities

WHY OBSERVE FIREBALLS AND STUDY METEORITES?

Rocky bodies in interplanetary space are of cometary or asteroidal origin. They are on different orbits to the Earth and can occasionally fly right into us. They can be travelling at speeds of up to 72 km a second and when they hit the atmosphere, it’s like someone turned on the brakes – they turn into a ball of fire. Small cometary dust usually burns up and never makes it to the ground. Asteroidal material can be bigger and, if the conditions are right, can survive the atmosphere and land on the ground as a meteorite. Some meteorites also come from larger planetary bodies, such as the Moon and Mars. Meteorites are special in that they preserve the histories of their parent bodies, giving us clues to planetary body formation and evolution over the last 4.56 billion years. Highly primitive meteorites contain some of the first solids to have formed in our Solar system and have changed very little since their initial formation. These have been used to date a more precise age of our Solar System (4.568 billion years).

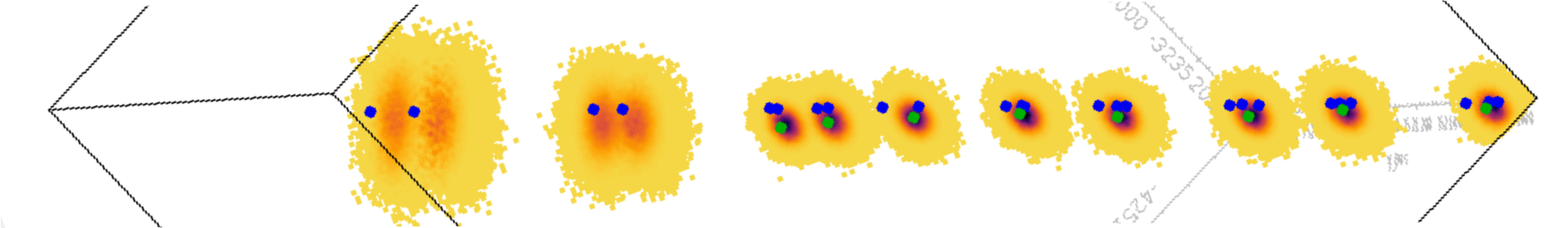

Meteorite falls observed using the DFN observatory helps to inform how a body interacts with the Earth’s atmosphere, how it decelerates, how bright the meteor is depending on the object, and the changes in mass whilst it falls. Observing the atmospheric trajectory of these bodies allows us to calculate their orbits and, if a meteorite is recovered, give us the key spacial context to the information it holds.

Fireball networks allow researchers to try and answer some really cool questions:

- Why are there different types of meteorites?

- Where did they come from in the Solar System?

- Can we make a geological map of the inner Solar System?

- Can we study samples from a known asteroid, like a sample-return mission?

- Are there such things as cometary meteorites?

- How did rocky planets form?

- Where did all the water and organics came from on the terrestrial planets?

Projects

Instrumentation

Meet the team who designs autonomous intelligent observatories, able to work in the Canadian polar winter as well as survive the Australian desert